Dissecting Lynch's Latest Atop Freud's Well Worn Sofa

WARNING: This article reveals plot elements which may spoil your experience when watching the film for the first time.

If its maker's goal was to baffle, Mulholland Drive, in expanded release nationwide, has done its maker proud. David Lynch, the mind behind cult classic, Eraserhead - which took critics years to figure out, and audiences even longer to appreciate - has once again confounded the experts - a category which includes critics, film geeks, Lynch obsessives - with its revolving door of a character-laden plot.

Don't get me wrong; nobody's grumbling significantly about this - the film has been widely well received for its captivating mystery and sheer juiciness. Yet examples of incomprehension are everywhere. Glenn Kenny, of Premiere, liked the film immensely, except for a minor rant: "What the hell happens in this movie?" Similarly, in his review for Film Comment, author Philip Lopate demands: "What gives? Is there a right solution, which only David Lynch knows?" Online, the Kansas City Star warns, "Don't even try to follow twisted Mulholland Drive." Entertainment Weekly's Owen Gleiberman calls the film's plot "a pretzel that never connects with itself." Roger Ebert declares, "there is no explanation," recommending that "if you require logic, see something else." The New Yorker's Anthony Lane concludes "the answer to [a character's] inquiries is... even less clear at the conclusion of the picture than it was at the beginning," and that the second part gets us "lost in a forest of hints and contradictions." And Stephen Holden, of the New York Times, asks, "who needs continuity if you can disappear into a dream?" He believes the film has "surrendered any semblance of rationality to create a post-Freudian... fever dream" with "disconnected... images" in "nightmarish relationship."

But ask a Freudian dream analyst, and you're likely to get a very different answer. I discussed the film with Dr. Frederick Lane, clinical professor of psychiatry and practician, who teaches dream analysis at Columbia Medical School. Unlike the film experts, Dr. Lane understood Mulholland Drive immediately as the product of a mind intimately familiar with dream analysis. When he shared his interpretation with me, stray plotlines clicked satisfyingly into place, filling in some interesting gaps.

It's true, as several critics have reasoned, that the film's broad-brush examination - into illusion, desire, control, and identity - should be neither obscured nor ignored in an examination of plot. Like other Lynchian films, Mulholland Drive resides deeply in the netherworld, a world that has more interest in breaking ground along Lynchian frontier (what lurks in our subconscious) than walking back over well-mined Lynch territory (what lurks beneath the surface). But to overlook a nearly flawless, if anachronistic, plot is to miss some important nuances which allow one to probe even deeper into the unconscious to examine, for example, the nature of lost love, jealousy, revenge, regret, guilt, and suicide.

As with Eraserhead, Mulholland Drive begs for multiple

viewings, in the attempt to discover whether it all makes sense.

Like Eraserhead, the effort is rewarded once you find, then

accept, the film's internal system of rules, As one would expect

from a top modern-day master of illusion, it's deceptively simple.

As one would not expect from a director who habitually flouts

logic in favor of metaphor and enduring mystery, it's 100% air-tight, from ground level up.

As with Eraserhead, Mulholland Drive begs for multiple

viewings, in the attempt to discover whether it all makes sense.

Like Eraserhead, the effort is rewarded once you find, then

accept, the film's internal system of rules, As one would expect

from a top modern-day master of illusion, it's deceptively simple.

As one would not expect from a director who habitually flouts

logic in favor of metaphor and enduring mystery, it's 100% air-tight, from ground level up.

First, a refresher course on Freudian dream theory. The mind works in mysterious ways, not least by showing each of us the equivalent of a movie or two on our way in and out of that rabbit hole called sleep. As Dr. Lane explained, a dream can inhabit the dreamer's viewpoint, It was more than a century ago that Freud concluded dreams to be a synthesis of images seen during the day (call it the day's "residue"), combined with hallucinogenic manifestations of deep-seated emotions and desires. Thus, fairly innocuous elements of actuality and truth (the day's residue) are tapestry-woven in with elements of fantasy driven more meaningfully by want or emotional need, resulting in a weird hybrid - the sensible hallucination.

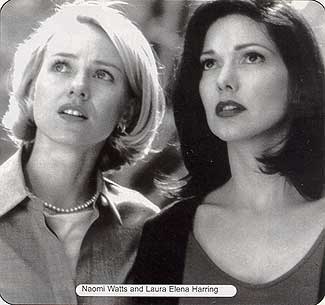

Plot speculation focuses on how the longer, initial sequence that identifies Naomi Watts' character as cheerful ingenue "Betty Elms" (we'll call this Part A) fits in with the subsequent, shorter sequence which identifies Watts as haggard depressive "Diane Selwyn" (Part B). At least one critic, Amy Taubin, cottoned on early to the film's greatest magic trick: Part A is nothing but "a classic anxiety dream that's part grandiose wish fulfillment and part prophecy of death" (Film Comment). Once conceived, this illusion is initially difficult to accept: as viewers, we are conditioned to believe the first edition of on-screen characters and storylines, particularly ones we have followed in more or less linear fashion for two hours. Given the lushness and camaraderie of Part A versus the bleakness and desolation of Part B, we'd rather Part A be true and Part B be someone's hellish nightmare.

Once digested, however, this grand illusion brings with it another twist - a clever reversal: Part B largely precedes Part A in time, in addition to trumping it in reality. In other words, Part B provides the back-story (the facts and circumstances supporting the dream that comprises Part A in its entirety) for Part A, the dream. Still with me? Flip the two parts around, and the film would begin with the events of a stressful day for frustrated actress Diane Selwyn.

Lying on bright coral sheets, she wakes to pounding at the door: an ex-roommate wants her things back. While the camera lingers pointedly over a blue key on the coffee table, the roommate tells Diane some detectives have been by to question her. When she's alone again, Diane goes about her morning routine. Dispirited by sorrow and distracted by memory, we follow her into the recent past. Diane is clearly still in love with a former lover, glamorous Camilla Rhodes (Laura Elena Harring). In a vivid masturbation sequence, Diane looks back upon their sex play, then Camilla's reluctance and cruelty, and their eventual breakup.

In a separate flashback, Camilla has insisted on Diane's attendance at celebration of Adam Kesher (Justin Theroux), the self-aggrandizing director of a film starring Camilla, with Diane in an inconsequential role. The party goes badly for Diane: distracted by the announcement, her small talk is meek and uncomfortable. She's marginalized, then watches, or imagines, Camilla give a lusty French kiss to a well-coiffed blonde. Jealous and deeply hurt, Diane hires a hit man the following day, handing him a wad of cash and Camilla's head-shot. He shows her a gleaming blue key, and tells her when the job is done, he'll leave it in an appointed place.

The presence of the key in Diane's apartment clues us in: the deed must be complete; Camilla has been killed.

That's not the entirety of Part B, but I'll stop there. In the film, all of this happens after we've viewed the dream that is Part A, but chronologically, it happens before Part A has taken place inside Diane's mottled, guilt-ridden mind. From this point onward, she enters dreamland.

In part A from the get-go, after credits and a cartoon-purple jitterbug sequence which magnifies, or mocks, or simply reminds us of, the glitter of stardom, Lynch whisks us into Diane's dreams, over the hump of her sleeping figure breathing the quickened breath of REM from between bright coral sheets. It is too soon for a first-time viewer to identify this as the bed of Diane the dreamer, whom we spot much later on in Part A as a rot-caked corpse discovered by her own alter ego in a premonition of, or resignation to, suicide.

In her dream, Diane borrows a name from a waitress she saw earlier at Winkie's (the name of the diner itself is Lynch literally clueing us in). With the bebop moniker "Betty," she's assumed a matching new personality brimming over with can-do spirit. Diane, as Betty, is ready to embark on her Freudian journey of hardly-latent desires. The first order of business for the frustrated starlet? Head for a new start - via a fresh arrival - in Los Angeles, replete with the well wishes of an elderly couple who can't wait to see her on the big screen. This is Diane's dream, and in it she can be any kind of actress. We'll revisit this in a moment.

Next, Diane's dream mind places the lusty target of her jealousy, Camilla, who has already jilted her in the "real" life of Part B, into a position of artificial vulnerability. Later events support the theory that this is not by way of punishing Camilla for her rejection, so much as it fulfills a desire of Diane's; she desperately wants Camilla to choose her, and makes it easy for the Dream-Camilla to do so by bestowing her with the need to be rescued. The dreaming Diane therefore bakes up a Camilla who's still alive, gets amnesia, and winds up frightened and codependent in the perfect hideaway love nest: a plush, abandoned courtyard apartment. (interestingly, Part B reveals Diane and Camilla's dynamic to be the opposite: one in which the older, fuller Camilla strikes a maternal note toward Diane's sullen docility.)

Innocuously conjuring the limousine she rode to the engagement party in Part B, Diane's dream mind places Camilla alone in the backseat of the same limo, and has her mimic her own line of protest when it comes to a halt: "We don't stop here." Replicating her real-world, Part B self, Camilla's voice exhibits a command it promptly loses for the remainder of Part A, reminiscent of the personality shift dream characters often make before they settle, if at all, into Freudian usefulness. The limo driver pulls a gun on Camilla, but angst-ridden by her guilt and affection, Diane's dream mind rescues Camilla from her own murderous plot, making her the only survivor of the violent accident to follow. As an amnesiac, Camilla (soon christened "Rita") will not only need Diane/Betty, she will repay her gratitude in clinging companionship and voluptuous flesh.

The dreaming Diane's next significant order of business is to persecute her rival, Camilla's hated fiance. In Diane's dream, Adam shows up with all the trappings of stability: in his own likeness, with his own name, and the pomp of his own personality, doing his own job and living in a house that looks exactly like his own high in the Hollywood Hills. Except, Diane's Dream-Adam is afflicted with a serious case of Worst Possible Luck. First, in another winking outsiders reference by Hollywood's best-known independent director, Adam gets stripped of casting autonomy by a mob-like studio network. He comes home to find his wife in bed with the pool man, and in his attempt to extract revenge, ends up with blotches of neon pink paint on his L.A.-hip black outfit. Diane's dream mind has not evoked this from thin air, but from Adam's divorce anecdote told at the engagement party.

Diane's revenge tale contains some of her dream's most surreal sequences, and Part A's most comical moments, including a little-headed giant who can determine the fate of Adam's film with a phone call and a nod of his recessive chin, a studio executive as picky about his espresso as his casting choices (played by composer Angelo Badalamenti, a longtime Lynch collaborator), a decrepit hostel run by an inordinately caring proprietor with a cattail moustache and the unlikely name of "Cookie," and, not least, a pedantic cowboy, emerging stiffly into the fluorescent dimness of his L.A. corral. (Adam's own incredulity could realistically mirror Diane's, particularly if she is having a lucid, or self-aware, dream.)

But back to Diane's career. As an actress, Diane gets complete wish fulfillment: in her dream she's so good at her first audition - one of the film's best sequences - that the wizened casting team trades high-fives of glee when she leaves the room. But when the mafia-cowboy control center compels Adam to hire a washed-out blond identified as "Camilla Rhodes" as his lead, Diane's dream conveniently divorces real-life Camilla's professional success, which she envies, from her persona, which she lusts after. In her subconscious, the Camilla she's in love with is not the same as the one who got the role she coveted most.

Also, in one fell swoop, Diane's dreaming mind separates merit from success, forming a convenient excuse for her own stalled career. And, as with everything in the film, it harkens back to love: the mantra repeated to Adam until he obeys it - "this is the girl" - refers as easily to thinking you've found the person you'll spend the rest of your life with. In Diane's jilted-eye's view, the mantra's commanding tones disintegrate in force, losing meaning. Before long, she's using the words herself to instruct her hired hit man when she hands him Camilla's photo: "this is the girl," now reads: the one I can't let go of.

Diane draws images of her dream from real events in her life, leaving behind a potential hopscotch trail of mix-and-match confusion. Thus, the blue key used by Part B's hit man becomes the stylized blue "key" to Rita's identity in Part A; the cash she pulls out of her black purse to pay him multiplies and reincarnates as illicit-looking cash in Rita's black purse; Adam's real-life mother (Ann Miller), the only person to comfort Diane through her tears of disappointment at the party, is the nurturing building manager in Part A; the phone and mosaic ashtray in Diane's real apartment stands in for one of the telephones along the Hollywood Mafia's chain of command. Various characters from the engagement party and from the street - like the man standing at the counter at Winkie's - take roles in Diane's dream. In Part B, after Diane's roommate informs her about the two detectives trying to find her, Diane's dream mind sends another duo - Betty and Rita - on a foot search for Diane Selwyn..

And even as it helps itself to generous servings from three major wishes, Diane's dream mind makes a gingerly attempt to process through, and step away from, the double whammy of guilt and regret. She's already "raised" Camilla from the dead. She goes on to imagine her hit man incompetently offing two innocent people. Rita's knee-jerk fear to men in dark glasses could be dream-code for Diane's fear of the law, now that she's a fugitive. Finally, encountering one's own dead body might be a way of facing the rot within one's soul.

But she fails to work it through, and in the last few moments of Part B, elicits a waking hallucination. Pulling characters from her dream - the elderly couple from the airport who return in sinister miniature, first behind Winkie's dumpster then in the crack under her door, to mock her ambition - Diane can no longer handle her overwhelming feelings of guilt, regret, and eventual fear (the thumping on the door may signify the police). As the couple, and Diane's paranoia, grow life-size and chase her into her own bedroom, she picks up a gun and shoots herself in the head, finally quieting - or achieving "silencio," the film's final utterance - within her hyperactive mind.

Clueing us into the dream, Lynch's tip-offs are frequent, but hardly dead giveaways. After Diane/Betty meets Camilla/Rita in Aunt Ruth's apartment, she says, "I just came here from Deep River, Ontario, and now I'm in this dream place." She means the apartment, but in retrospect she's referring to her own dream. (incidentally, "Deep River" was Dorothy Valiens' home in Blue Velvet.) And the constant references to identity carry the same quiet message: when Louise the psychic neighbor volunteers a prediction of trouble, she tells Betty her name's not Betty, as though Betty, not Rita, were the one with amnesia. When Betty talks Rita into making inquiries about the car accident on Mulholland Drive, she assures her, "It'll be just like in the movies: we'll pretend to be someone else."

The most obvious, the sequence in the performance hall "Silencio," is fraught with entendre: more intense than a mere hint, Lynch nudges us forcefully in the ribs. His message? It doesn't matter whether the illusion you interpret is the music on the stage, the dream itself, which is about to come to an end, or all films and all of cinema. What's most disturbing isn't the fact of the illusion or fantasy, but its power to move audiences - here, Betty and Rita, suddenly proxies for a universal group - to tears, even to fell the feigning performer herself. It's a frightening power, especially when it can be evoked without any real sensory input (the pre-recorded song is lip-synced). When Diane commits suicide, it's an extension of this: she's ultimately "felled by" the guilt and regret manifested in something which lacks, but proves more powerful than, sensory reality: her dream.

Clueing us into the suicide, Lynch's tip-offs are no less subtle. The heavy-browed man who tells his friend about his nightmare in Winkie's serves two purposes: by mentioning the word "dream," he's tossing us a hint, but his own fate becomes allegorical - to viewers, to Diane - in relation to fear and guilt. He leans close to his friend and confides his desire to "get rid of this god-awful feeling." We don't know what he may have done to deserve the feeling, or even what the feeling is beyond raw fear, but he never man- ages to get rid of it. Instead, he comes face to face with his nightmare apparition, the source of his fear, a scarred face that looks awfully close to Death... and drops dead. As she attempts to process guilt, Diane's dream mind may be televising death, or suicide, as an inescapable solution.

Similarly, Rita is disappointed when sleep fails to cure her amnesia: is Diane disappointed after her nap, when sleep failed to 'cure' her guilt? When Mr. Roque, the little-headed giant, orders his peons to "shut everything down," Diane's dream mind might have been reaching for the same question, pondering suicide as an option.

Lynch delineates Part A, the protracted dream, in tone and texture as much as content. Replicating the eerie aura of dream, except for an occasional low industrial hum accompanying tires along a sinuous road, Part A for the most part lacks soundtrack. The camera moves sensually across imagery with too much garish clarity to be real: in contrast, Part B, set to music, looks grainy and grungy. Whether because of its network roots or because of the dreamlike aura, everything in Part A seems to happen in slow motion: establishing shots, pacing, dialogue.

But according to Dr. Lane, "the film imparts an aura more Lynch-like than dream-like." Dense as vivid dreams seem when recalled, a mind transitioning to a waking state adds narrative to the bare-bones, kaleidoscopic blueprint that comprises most dreams. What took two hours to portray could have easily been a real, 20-minute dream after the rational mind colors it in with explanation, rationale, and the laws of physics - and winds up with a manifest dream.

And like Mulholland Drive, or any dream unspooling, films and dreams offer the ultimate fantasy freedom - sensory experience without attachment, with only one proviso: You've got to be able to live afterward with the waking memory. <<

Jean Tang is a journalist who writes about film and her hometown, New York City.

Copyright 2001 7DazeMedia, LLC

Back to the Mulholland Drive articles page.