The mind behind MULHOLLAND DRIVE leads a tour through his twisted body of work.

by Jeff Jensen

The mind behind MULHOLLAND DRIVE leads a tour through his twisted body of work.

by Jeff Jensen

There's a dismembered bird's wing on David Lynch's desk. It's large and dirty and molted and just lying there, soaking up the sunshine that's pouring in through the windows of his hilltop painting studio in Los Angeles. The 55 year-old filmmaker, clad in khakis and a buttoned to-the-neck dress shirt and burning through cigarette after cigarette, says nothing of the grim object resting between him and his interviewer, as if its presence requires no explanation. But since dirty dismembered bird wings lying inexplicably on desks are, as a general rule, rather strange, you feel compelled to ask, and when you do, he smirks. "My assistant found this the other day and brought it to me," says the Montana native in his Western twang. "Sometimes I put stuff in my paintings, and he thought I could do something with it." Of course he could: After all, this is the oddball auteur who made a severed human ear the haunting central image of his 1986 masterpiece Blue Velvet. In fact, his ninth and latest feature, the trippy-sexy neo-noir Mulholland Drive, which opened to strong reviews and promising grosses on Oct. 12, is a cinematic salvage act, combining parts of a failed 1999 ABC pilot with footage shot last year. The result, which earned Lynch a shared best director honor at last spring's Cannes film festival, is Frankenstein created by a mad scientist under the influence of Vertigo and Sunset Boulevard (two of Lynch's favorite films).

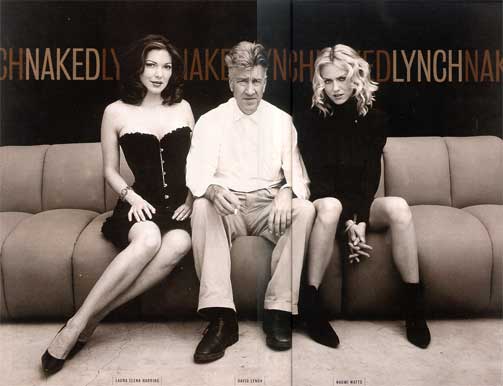

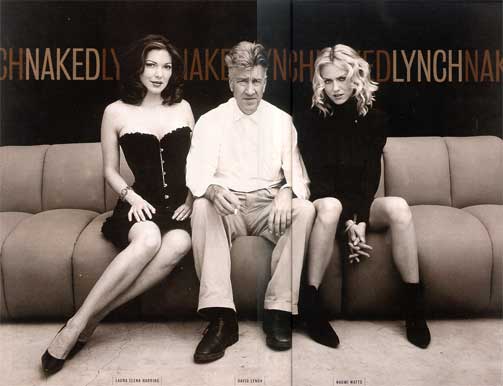

Drive is the twisted tale of a wide-eyed aspiring actress named Betty (Naomi Watts) whose life gets intertwined with a ravenhaired amnesiac (Laura Elena Harring) searching for her true identity. In between auditions, Betty plays Nancy Drew with her dusky new friend, and their investigation ultimately leads to a bloated corpse, a mysterious blue box, and a role-swapping denouement that defies rational analysis. Even his stars were befuddled when Lynch reconvened them last year, long after the shooting of the pilot. "I remember the day when David told Naomi and me,'Ladies, Mulholland DIrive is going to be an international feature film!"' recalls Harring,

perfectly nailing Lynch's accent. "We were so happy, but it wasn't until we left that we looked at each other and went, What exactly did we just agree to in there?" Adds Watts: "I would really try to siphon whatever I could out of him, but when he wouldn't give, I'd be like, 'Why are you doing this to me?' He was almost delighting in my torture!"

Drive is the twisted tale of a wide-eyed aspiring actress named Betty (Naomi Watts) whose life gets intertwined with a ravenhaired amnesiac (Laura Elena Harring) searching for her true identity. In between auditions, Betty plays Nancy Drew with her dusky new friend, and their investigation ultimately leads to a bloated corpse, a mysterious blue box, and a role-swapping denouement that defies rational analysis. Even his stars were befuddled when Lynch reconvened them last year, long after the shooting of the pilot. "I remember the day when David told Naomi and me,'Ladies, Mulholland DIrive is going to be an international feature film!"' recalls Harring,

perfectly nailing Lynch's accent. "We were so happy, but it wasn't until we left that we looked at each other and went, What exactly did we just agree to in there?" Adds Watts: "I would really try to siphon whatever I could out of him, but when he wouldn't give, I'd be like, 'Why are you doing this to me?' He was almost delighting in my torture!"

Maybe--or maybe he just didn't know what to say. Likening his creative process to that of the Surrealists, Lynch says all his movies "are made of ideas, strung together and forming a story and the world that comes with it. And I've always believed that if you remain true to the ideas, more often than not, that whole will hold together just correct."

Trusting in his gut has produced one of cinema's oddest oeuvres. Lynch became intrigued with filmmaking in the late 1960s while attending the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. After getting a grant from the American Film Institute for a 16mrn short called The Grandmother (1970), he enrolled at AFI in Los Angeles and soon began working on his first feature-length effort, Eraserhead.

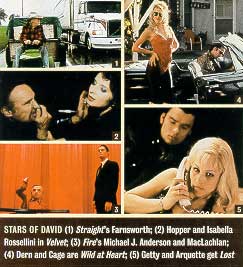

THE FILMS:

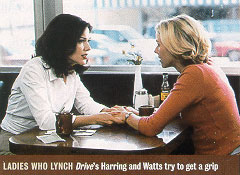

ERASERHEAD (1977)

A shock-haired hero loses his

head (literally), kills his fish-eyed

child, and escapes into a radiator

where an angelic, lumpy-faced

lady lives. Maybe. All that was to

become "Lynchian"--dreamlike

narrative, freak-show characters,

ominous soundscapes, deadpan

detachment-was present in his

first feature. Lynch shot overfour

years, living and working in unused horse stables owned by the

AFI.

"It was like I died and

went to heaven. It looked like

stables from the outside, but inside it was another world. I know

ideas came from living in there

that wouldn't have come if we had

the money and could go faster. I

always think about doing a film

jike that again; there's something

about a small, intimate crew, living in a world for a long period of

time. There's just something

about it-the moving slowly."

THE ELEPHANT MAN (1980)

THE ELEPHANT MAN (1980)

Lynch wanted to follow Eraserhead with the equally weird Ronnie Rocket, but couldn't find financing. Enter Mel Brooks,

whose production company was

searching for a director for a Victorian-era drama based on the

true story of the grossly deformed

John Merrick. The inspired pairing of sensibility and material

yielded a box office hit and eight

Oscar nods (including Best Picture and Best Director).

"The whole thing would never have

happened without Mel Brooks. I

didn't have final cut, but he in effect gave me final cut. When [studio execs] wanted to alter things,

he became the most powerful lion

and just devoured these enemies.

Pressure? On the first day, [actress] Wendy Hiller grabbed me

by the neck and walked me

around, saying, 'I don't know you.

I will be watching you.' It was that way throughout - heaven

and hell, thrown together."

DUNE (1984)

Many offers came Lynch's way

after The Elephant Man, including Return of the Jedi. Instead,

Lynch fatefully chose to adapt

Frank Herbert's sci-fi epic for

Uber producer Dino De Laurentiis Lambasted for its incoherence, miscasting (a then-un-

known Kyle MacLachlan made

his debut as a desert messiah),

and dingy veneer, Dune nearly

killed Lynch's career.

"You don't

really know until it's too late. But

you know the expression, 'Well

begun, half done'? It wasn't well

begun. From the beginning, it

was a slippery slope that kept go

ing downwards. I was two people: One that put one foot in front

of the other and does the work,

while the other one is right above

it, going insane. It wasn't pleasant. Still, I had no one to blame

but myself. I learned a lot from

that experience. Most importantly? Get final cut."

BLUE VELVET (1986)

What a comeback. Lynch made a

deal with De Laurentiis, giving

up half his fee in return for total

control of his next project. Starring MacLachlan as a college kid

whose voyeurism gets him into

big trouble with Dennis Hopper's

sadistic criminal, Blue Velvet

earned Lynch a second Best Director nomination. Legend has it

that he giggled while watching

Hopper performing in the film's

deeply disturbing rape sequence.

"If you believe in your work,

nothing can hurt you. But if you

don't believe in it, and it comes

out bad? Double whammy. That

was me after Dune. So with Blue

Velvet, there was nowhere to go

but up. I had euphoria in freedom

and it was beautiful. As for the

laughing story, it was like a dog

in a chocolate shop. It just starts

eating that chocolate and there's

no stopping it, it's just so obsessed. So to see Dennis just so

obsessed, so focused like that-it

just made me laugh."

WILD AT HEART (1990)

Starring Nicolas Cage as an

Elvis-idolizing rogue and Laura

Dern as a trashy Southern belle,

Lynch's hyper-pop romance won

the Palme d'Or at Cannes. But

the film was criticized in the U.S.

for its self-indulgence and extreme violence. It could have been

worse: To get an R rating, Lynch

had to cut a torture scene and obscure a shot in which Willem

Dafoe's head gets blown off.

"At that time, [Barry Gifford's] book

married with a feeling I had - a

feeling that the world was going

insane. But I did cross the line in

my first cuts; I was kind of pushing it to this place I felt was real,

but it was very sick and insane.

When 300 people out of 400 leave

the theater [during a test screen-

ing], for the sake of the whole,

you adjust! I've found the ratings

board wants to work with you.

They just say, 'We don't want to

tell you what to do, but if you can

help us, we would like that.'

Here, they were right."

TWIN PEAKS: FIRE

WALK WITH ME (1992)

TWIN PEAKS: FIRE

WALK WITH ME (1992)

In October 1990, propelled by the

success of his TV series Twin

Peaks, Lynch found himself on

the cover of TIME magazine.

"Someone told me a TIME cover

curses you with two years' bad

luck," says Lynch. "That's what

happened." It kicked in the following spring, when Twin Peaks

was canceled, and continued into

Lynch's movie prequel, which

fans rejected for not resolving the

series' many riddles.

"I never

even thought about tying up the

loose ends. I wanted to go into

the last seven days of Laura

Palmer, and all the ideas came

out around that thinking. There

were other scenes shot that didn't

end up in the film, but they didn't

fit into this particular story. But

those were the days of the curse,

so I sort of knew it wouldn't go

over. Yet I loved the film, so it

didn't hurt me. So there it is."

LOST HIGHWAY (1997)

With a looping narrative similar

to Mulholland Drive's, Lynch's

noir/horror hybrid tells the twisted tale of a jealous husband (Bill

Pullman) who's convinced his

wife (Patricia Arquette) is cheating on him. After being convicted

of her murder and jailed, Pullman escapes - into the head of

Balthazar Getty. Then things really get weird. If you view it

again, keep this in mind: "Looking back now, I see that Lost

Highway was hugely influenced

by O.J. Simpson. Ask yourself:

How can O.J. golf? How can he

even hit the ball? How can he

even go out of bed in the morning? How does the mind seal itself off from horror and be able to

live and think and hit a golf ball?

So when you think about that,

and you think about Lost Highway ... it sort of makes sense!"

THE STRAIGHT STORY (1999)

Perhaps Lynch's most surprising

film: a sweet, decidedly linear fable based on the true story of an

old man (Oscar-nominated Richard Farnsworth) who traveled

across Iowa on a tractor to reconcile with his ailing brother. Free

of sex, violence, and ironic detachment, the sublime Story

shocked even the director's most

hardcore fans - by winning a G

rating. Some were moved to ask,

Just what is a David Lynch film?

"Who knows? [Laughs] It's ideas

that have passed through my machine. It's not just music. It's not

just pace. It's not just 'a look.' It's

a combo of things that have to be

correct. It reminds me of a symphony, when they have different

movements, and what goes before is critical to a big moment

coming up. So many things have

to be correct. Too little, it doesn't

happen; too much, it breaks it. So

it's a tricky business, making

movies. Just a tricky business."

© 2001 Entertainment Weekly Inc.

Back to the Lynch articles page